Oct 20, 2015 | English, European Union, Human rights, International migrations, Passage au crible (English)

By Catherine Wihtol de Wenden

Translation: Lawrence Myers

Passage au crible n° 132

Source: Pixabay

Source: Pixabay

In 2014, the EU received 625,000 asylum seekers, a figure not seen until then. Previously, the yearly number remained around 200,00 applications. In 2015, 300,000 people from around Europe (Libya, Syria, Iraq, the Horn of Africa) were forced to migrate due to the chaos facing their countries. Besides these facts, the drowning deaths of two thousand people at the borders of Europe are also deplored. Yet, the data continues to worsen. Between 2000 and 2015, an estimated 30,000 people perished in the Mediterranean. The overall number since 1990 stands at 40,000. At the same time, Angela Merkel’s speech in September 2015 was an unprecedented turning point. The German Chancellor announced that Germany was ready to host 800,000 asylum seekers in the coming months. For their part, French President François Hollande and the President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Junker, are calling for the creation of a permanent and compulsory system of reception of asylum applications in all European Union member states according to each country’s population and resources.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

The European asylum policy based on the 1951 Geneva Convention defines a refugee as a person fleeing persecution or experiencing legitimate fears. This condition being met, he or she may then apply for a home in a host country. The right to asylum is a universal right that only fifty countries have not yet accepted. But given the diversity of responses of European powers, the EU is continuing to seek to harmony on this topic.

The first instruments of harmonization were used during the first asylum crisis in Europe after the fall of the Iron Curtain. At the time, 500,000 asylum applicants were sent to the European Union (including 432,000 in Germany in 1992). At that time, there was a struggle against “asylum shopping” where applicants made requests to various members of the Union pending on the response from the highest bidder. From now on – and this was at stake during the 1990 Dublin agreements – one single application is acceptable for treatment and response from all EU states. The same goes for the acceptance or refusal of granting refugee status. Since applications were addressed to Germany and Austria during this period, they have requested a sharing of the “burden”. This finally resulted in the Dublin II agreement in 2003. Itself based on the “one stop, one shop” principle. In this case, this means those concerned must now seek asylum in the first European country where they arrive. However, this logic has led to a backlog of applications on state territories located along the external borders of Europe, such as Italy and Greece, poorly equipped to cope with the influx of refugees. In addition, these states have a lesser culture of asylum, unlike Germany or Sweden. Newcomers have sought to leave, firstly avoiding the stamping of their passport. Doing so has kept them from being inevitably sent back to their first country of arrival. Such regulation has brought many locations to a point of saturation; including Athens or Calais and Sangatte in France. Applicants awaiting asylum in the United Kingdom are camping out in these two French cities.

In 2008, the European Pact on Immigration and Asylum (which is not a treaty) stated, among its five principles, the harmonization of European asylum law. It is in this spirit that an office in Malta was created, to harmonize the answers based on applicants’ profiles. A list of safe countries as well as other areas of safety under the control of non-state organizations, and a notification of clearly unfounded applications has therefore passed between members of the Union. This is a state of affairs that has come to restrict all chances for obtaining refugee status. But the Arab revolutions of 2011, the Syrian, Libyan and Iraqi crises combined with the arrival of many Afghans, eventually rendered the Dublin II regulation meaningless. A new, more tolerant practice then allowed the circulation of asylum seekers towards territories where they wanted to go. It also offered more flexibility in determining the processing and application country, depending on the applicant’s choice and its links with a particular European region. This turnaround recently mentioned by Angela Merkel will without a doubt lead to the disappearance of the Dublin II regulation.

Therefore, we note that 2014 and 2015 saw an exceptional influx of asylum requests. Faced with this challenge, the quota proposal made by the European Commission, which was initially snubbed in June 2015, was then followed by a compulsory system. It has now led to a new line between two groups of Europeans. On the one hand, those who accept to welcome refugees, and on the other hand, those who refuse the imposition of such measures such as the Central and Eastern European States, the United Kingdom, Ireland and Denmark.

Theoretical framework

1. Asylum confronted with the influx of Syrians. Should the Geneva Convention still be respected terms of assessing the individual character of an asylum seeker’s profile and the persecution that he or she has gone through or that she or he is fleeing? Should we not make a collective response adapted to this group of people of whom six million have fled their homes since 2011 and four million are abroad today? Some countries have already agreed to host millions of Syrians. They primarily include Turkey: 1.8 million; Lebanon: 1,200,000; and Jordan: 600,00. In other words, the urgency of this crisis does not require an exceptional response to an exceptional situation, as was the case in the past for the Vietnamese, Cambodian and Laotian boat people, between 1975-1980? There is also the question pertaining to the sovereignty of European countries. Many are having trouble accepting that asylum seekers are imposed on them. Mechanisms such as temporary protection, based on the European directive of 2001, could be applied, as in the past for citizens of the former Yugoslavia. However, these provisions are not part of the proposed solutions.

2. The harmonization of asylum in the European Union. In this political community, each country sets up its own diplomacy. Each has a special relationship with a particular country of origin and whether it maintains its tradition of asylum, given the low visibility of the Union’s common policy. Yet, asylum seekers often have a clear idea of the country where they want to go, for reasons of language, family ties, employment opportunities and benefits. Therefore, the idea that member states would all be seen as similar to them remains purely a pipe dream. In this context, the public opinion on the extreme right has long held that the practice of responding to European countries by affirming their policies here and there without restrictive nuances, exploits this issue which is in the service of migration security policies.

Analysis

The asylum crisis that Europe is currently facing shows that deterrence has reached its limits. Although over the past 25 years it has been the strategy of choice and has seen the continual sophistication of its instruments, this strategy has not reduced regular and irregular entries or lessened the number of requests for asylum. Rather, it emphasizes the existing lines that are currently dividing Europe, between countries in the East and those in the West. Thus, this situation reveals the hostility of the new EU members from the communist bloc. It also renews the disparities between the North and the South. These differences are illustrated by the lack of solidarity between northern European countries – little affected by the arrivals in southern Europe – and states like Italy and Greece. So far, the latter have welcomed the bulk of those arriving. This we saw in Italy with Operation Mare Nostrum, implemented between November 2013 and November 2014. Ultimately, withdrawal wins out on account of EU solidarity principles. However it must be understood in this connection that Europe places its values on this human rights issue and on the shared responsibilities in the decision to welcome – or not to welcome – refugees.

References

Höpfner Florian, L’Évolution de la notion de réfugié, Paris, Pédone, 2014.

Vaudano Maxime, « Comprendre la crise des migrants en Europe en cartes, graphiques et vidéos », LeMonde.fr, [En ligne], 4 sept. 2015, disponible à l’adresse suivante : http://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2015/09/04/comprendre-la-crise-des-migrants-en-europe-en-cartes-graphiques-et-videos_4745981_4355770.html. Dernière consultation : le 17 sept. 2015.

Wihtol de Wenden Catherine, La Question migratoire au XXIe siècle. Migrants, réfugiés et relations internationales, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2013.

Oct 13, 2015 | China, Diplomacy, English, International commerce, International Finance, Multilaterism, Non-state diplomacy, Passage au crible (English)

By Justin Chiu

Translation: Lawrence Myers

Passage au crible n°131

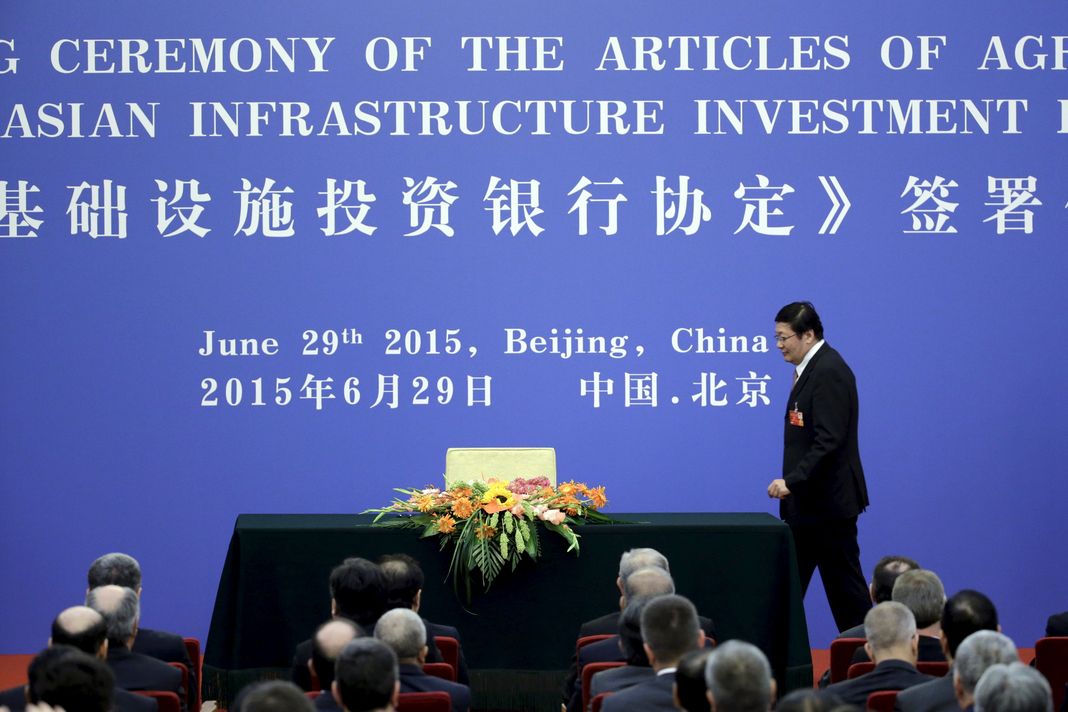

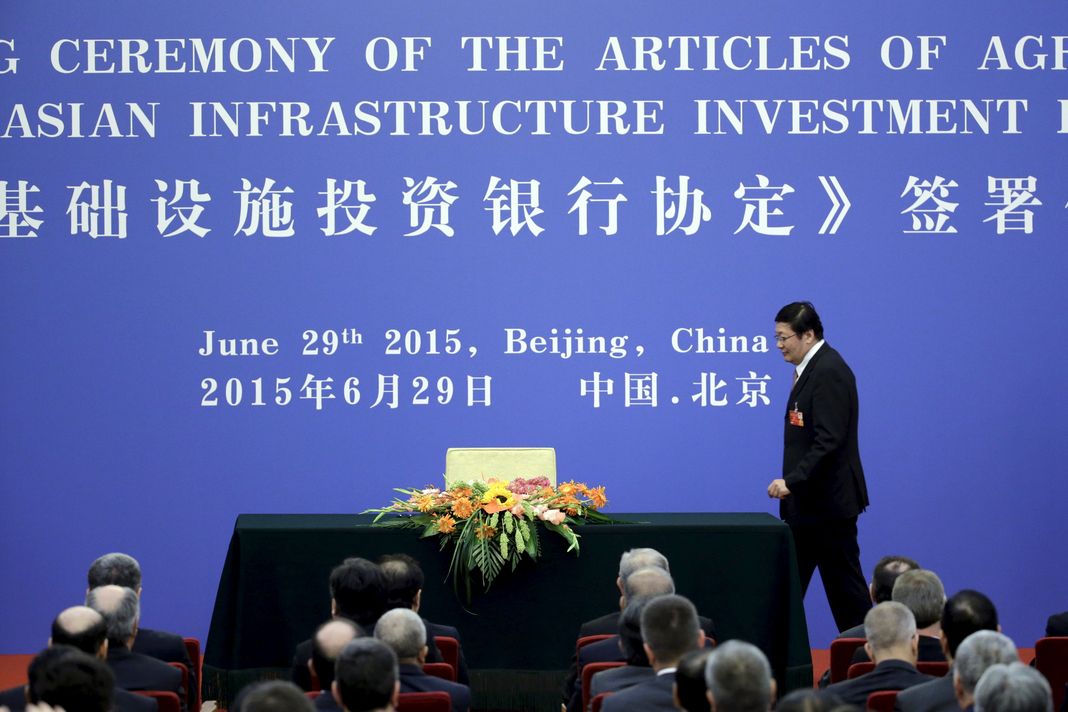

Source: Jason Lee / Reuters pour Le Monde

Source: Jason Lee / Reuters pour Le Monde

On June 29, 2015, the signing ceremony of the statutes of the AIIB (Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank) was held in Beijing. Bringing together 57 countries worldwide, this new multilateral bank has established a $100 billion fund of which 30% comes from China. Considered a diplomatic success of the Chinese state, the creation of the AIIB marks a turning point in global finance.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

In September 2013, six months after taking power, Chinese President Xi Jinping presented his overall economy and trade strategy, which bore the title The Eurasian Land Bridge (also called the New Silk Road). In order to secure access to raw materials and streamline the exportation of goods, priority is now placed on strengthening transport networks – both land and sea – and communication between Beijing and its partners in Asia and Europe. However, according to the ADB (Asian Development Bank), a yearly sum of $800 billion would be required to support infrastructure construction in Asia. But the World Bank and the ADB can finance only 20 billion dollars. The draft unveiled by AIIB in October 2013, is indeed a political maneuver. It comes primarily as a response to economic necessity.

Since its accession to the WTO (World Trade Organization) in 2001, China has multiplied its exchanges and especially its trade surplus (382.46 billion US dollars in 2014). In March 2015, Beijing’s foreign reserves accumulated and amounted to 3.730 billion. The first bearer of US government debt with 1.277 billion dollars in Treasury bills (July 2013), today China also invests in the European debt through the ESM (European Stability Mechanism). Nevertheless, to diversify and strengthen the partnership with the South, China has created several transnational organizations, such as the China-Africa Development Fund (2006). This desire to export more capital than manufactured goods, is also expressed by the ongoing establishment of the AIIB in Beijing and that of BRICS Development Bank in Shanghai. Moreover, the role of Eximbank and CDB (China Development Bank) were reinforced by bilateral projects. In this regard, Beijing lent $73 billion to its partners in Latin America for the period 2005-2011, while the World Bank lent 53 million.

Theoretical framework

1. The Transnational Offensive of a Competition State. According to Philip Cerny, the competition State has gradually replaced the welfare State to meet the requirements of global competition. Indeed, in the policy process, the State is now forced to find harmony between domestic requirements and international goals. By the transnationalisation of their activities, networks and strategies, State actors could benefit more from globalization and safeguard the interests of private groups. Thus, contrary to the view of the retreat of the State put forth by Susan Strange, Cerny notes that in some economic-financial areas, State power sometimes multiplies its interventions.

2. The financialization of relationships of domination. In Philosophy of Money, Simmel demonstrates the key role of the monetary economy in the densification of trade. In fact, with money, abstract action among individuals and social groups becomes measurable and concrete. Monetized exchanges therefore reinforce interdependence and domination. In this regard, the capital holder has the power to impose conditions and to assign him or herself privileges. Thus, money becomes synonymous with power.

Analysis

Rich in natural and mineral resources, China nevertheless remains the first importer in the world of these very elements. In order to secure its supply of oil, it is involved in infrastructure construction in Africa (Angola, Nigeria, Sudan and South Sudan), Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan), but also more recently in Pakistan, with a large, $46 billion investment program. Regarding the development of energy industries and transport networks, AIIB is to consolidate the efforts already made by the government in Beijing.

Curiously, Chinese firms will be the primary beneficiaries of the AIIB’s investments. In fact, the oil companies – CNOOC (China National Offshore Oil Corporation) and Sinopec (China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation) – the largest construction companies – CSCEC (China State Construction Engineering Corp) – and Huawei telecom equipment manufacturers and ZTE jointly gained experience in this kind of complex work linking energy and transport networks. Supported by major Chinese banks, they are able to respond to tenders with very competitive rates. They are counting on additional long-term benefits. In addition, as a shareholder that holds 30% of the company and 26% of voting rights, Beijing could enforce its decisions in this new financial mechanism. In other words, by the export of capital, the Chinese state seeks to support the internationalization of its companies.

Despite pressure from Washington, its western allies and Tokyo’s distrust, Beijing has managed a diplomatic feat. In fact, after an application for membership by the United Kingdom filed in March 2015, Germany, France, Italy, Spain and twelve other European countries have also submitted their requests. Regional actors, Brazil, Egypt and South Africa are also founding members of the new bank. Although the participation of non-Asian countries is limited to 25% of the capital, the essential thing for these States is to not be excluded. All the more as the economic benefits seems significant. Also, to define the governance of the AIIB and assess the viability of projects, China does not need financial expertise from outside.

Anticipating the growth momentum in Asia, establishing the AIIB produced a multiplier effect. ADB – to which Japan is the largest contributor – promised to increase its own funds, which will allegedly rise from 18 to 53 billion dollars in 2017. The scale of the work could be measured by capital flows. Finally, with the creation of this multilateral bank, the Chinese government intends to open untapped markets and to highlight its indisputable leadership in Asia.

References

Cabestan Jean-Pierre, La Politique internationale de la Chine, Paris, Presses de Science Po, 2010.

Cerny Philip G., Rethinking World Politics: A Theory of Transnational Pluralism, New York, Oxford University Press, 2010.

Meyer Claude, La Chine, banquier du monde, Paris, Fayard, 2014.

Meyer Claude, « Le succès éclatant, mais ambigu, de la Banque asiatique d’investissement pour les infrastructures », Le Monde, 1 July 2015, available at :

http://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2015/07/01/le-succes-eclatant-mais-ambigu-de-la-banque-asiatique-d-investissement-pour-les-infrastructures_4665869_3232.html

Simmel Georg, Philosophie de l’argent, [1900], trad., Paris, PUF, 2009.

Official website of the AIIB: http://www.aiibank.org/

Jul 27, 2015 | environment, Foreign policy, Global Public Goods, Globalization, Multilaterism, Théorie En Marche

A few months before the COP21, the book by S. Aykut and A. Dahan offers readers valuable insights into the issues related to climate change negotiations.

In clear yet dense language, this manual retraces each and every steps of the construction of the climate regime, since the first warning signs until the Copenhagen Summit. The reader will discover the leading role played by the United States, both in the scientific field and concerning the formulation of policy linked to the problem. The meticulous explanation of the struggles to provide an appropriate framework will particularly allow for understanding of the persistence of numerous disagreements.

In light of the obvious failure of attempts to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, the authors question the reasons for such inefficiency. Indeed, it results from the gap that has been progressively growing between a “process of governance by the UN [ …] and furthermore, a reality punctuated by the bitter struggle for access to resources [..] and fossil energy”.

Aykut Stefan A., Dahan Amy, Gouverner le climat ? Vingt ans de négociations internationales, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2014, 749 pages including an 83-page bibliography, a list of acronyms as well as an index of graphs and tables.

Jul 26, 2015 | Climate change, English, environment, Globalization, Non-state diplomacy, Passage au crible (English)

By Weiting Chao

Translation: Lawrence Myers

Passage au crible n° 130

Source: Wikimedia

Source: Wikimedia

Six months before the Climate Conference (COP21), the 26th World Gas Conference (WGC2015) was held June 1-5, 2015, in Paris. Organized by the IGU (International Gas Union), the event brought together more than 4,000 representatives from 83 countries from the biggest global industry players including BP, Total, Shell, ExxonMobil, Chevron, ENI, BG Group, Statoil, Qatargass, PetroChina, etc. Climate change, which now takes center stage, incited these actors to discuss themes linked to energy transition.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

Negotiations between states concerning global warming began at the end of the 1980s. During the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, 153 countries signed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). In 1997, signatory countries adopted the Kyoto Protocol, which still to this day, continues to be the only binding agreement for developed countries to reduce their GHG (greenhouse gas) emissions between 2008 and 2012. From the moment the protocol came into force 2005, the post-Kyoto period was evoked. However, the signature of the new treaty is still proving to be difficult, as even after the failure of Copenhagen (COP15), in 2009, no significant progress towards a universal treaty has been observed. As a result, in 2012 in Doha, the Kyoto Protocol was extended until 2020. As for the adoption of a new treaty, it was postponed until COP21, which will take place in Paris in December 2015.

A few months before the event, WGCPARIS2015, the most important global gathering of the oil and gas industry, also took place in Paris. Discussions included the market value of the gas chain, exploration and production, international transmission, energy innovation, etc. During the summit, the companies underlined the crucial role of natural gas, which according to them produces two times less CO2 than coal. As such, it could help decrease GHG emissions. Moreover, on June 2 of this year, six European oil company executives (Shell, ENI, BP, BG group, Total and Statoil) wrote an open letter in Le Monde to encourage all state actors to collectively fix carbon price in order to promote energy efficiency. They also requested that the UNFCCC executive secretary assist them in holding a direct dialogue with the UN and Party countries within the context of COP21.

Theoretical framework

1. A Triangular diplomacy. Since the advent of a globalized market and the accelerated pace of technological change, states no longer control but a small part of the production process and direct less and less trade. However, today large energy groups hold a decisive position and act as political authorities, sometimes to the point of competing with governments. This transfer of power in favor of economic operators has led to the emergence of a few diplomacy based on the entanglement of three types of interactions: state to state diplomatic relations, state to firm and firm to firm. Indeed, in many situations, the negotiations that they hold amongst themselves often seem more important. Thus, the results of their negotiations strongly influence the direction of public policy.

2. The paradox of offensive protectionism. In a free market context, large companies maintain interventionist policies aiming to monopolize their portion of the market. Thus, they agree amongst themselves to limit their production, fix prices, agree on their respective market share and promote political, technical, economic and industrial progress. In short, they aim to create an international cartel. Therefore, these majors forge institutional arrangements, and then determine a source of international authority. Free and open competition, is therefore hampered; potential buyers have no other option than to accept the situation, in other words, to submit to it.

Analysis

Concerning energy, the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases produces around 35% of emissions, of which more than 56% come from oil and gaz. According to the IEA (International Energy Agency), efforts in this sector to reduce greenhouse gas remain essential. On the one hand, states require the cooperation of firms. On the other hand, as operating costs and benefits in this area appear to be significantly affected by new regulations, many of these operators are seeking to directly influence government decisions. As such, during the first negotiations, which were held in the 1990s, the vast majority of western petrochemical industries declined to adopt the reduction of CO2 emissions imposed by governments and furthermore, opposed any timetable related to their reduction. Organized primarily by the GCC (Global Climate Coalition), they managed to significantly slowing the process by obtaining agreements when negotiating the UNFCCC and Kyoto Protocol. With government power, ostensibly eroded, entrepreneurial pressures were a considerable obstacle to climate policy. However, at the end of the decade, industry support for the GCC has gradually faded. Several of its key members, such as BP and Shell, for example, have left the organization. Finally, in 2002, after thirteen years of operation, the GCC was officially dissolved. The virtual disappearance of anti-climate groups reflects a general trend of firms that become increasingly cooperative. Indeed, organized associations, into cartels, direct these significant changes arising from technological innovations and economic benefits either overtly or covertly. Thus, the IGU, founded in 1931, has more than 140 members representing 95% of the global gas market. It includes OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) companies, western super-majors as well as new oil giants in emerging countries such as PetroChina. Every three years, these companies gather at the World Gas Conference in order to establish a common strategy. The key criteria are decided in negotiations where the big oil companies play a predominant role. Fundamentally, these standards have fostered the development of new types of businesses for which potentially high profits – such as renewable energy, manufacturing innovations, new modes of transportation and intellectual property are projected.

This year, companies have forcefully shown how natural gas, which they claim to be the cleanest of fossil fuels, would form the principal vehicle for a good energy transition. The increased use of this resource could bring substantial capital into an emerging sector still fragmented and disorganized. Note that more than $670 billion was spent in 2013 to explore new reserves of fossil fuels. Moreover, the acquisition of BG Group by Shell, the amount of the transaction amounted to 47 billion pounds (64 billion euros), is an exceptional deal. With this merger, Shell – already very active in the field of gas – will increase production by 20% and its hydrocarbon reserves by 25%; besides that this super-major is already spending billions for exploration of the Arctic and projects related to the oil sands of Canada. Now, according to a recent analysis published by the journal Nature, the latter two projects are incompatible with the prevention of climate change, considered hazardous. Moreover, with the energy transition, a considerable amount was paid in order to invest in infrastructure such as the construction of the gas pipeline. In the United States, from 2008 to 2012, the amount of electricity generated from natural gas increased by over 50%. If current trends continue, this energy should account for nearly two-thirds of US electricity by 2050, consequently causing a massive renewal of equipment.

As for the introduction of a carbon pricing system that applies to all countries, firms gather around a common interest, namely the proper functioning of market mechanisms and the development of related regulations. Several companies actually use an internal carbon price to calculate the value of future projects and guide decisions on investment. In these circumstances, the price of carbon, which certain companies have already fixed, assumes, if it became the market price – a much stronger impact than the policies pursued today by governments.

Spokespeople for the gas industry, the major energy sector companies have presented their objectives not only to states but also to the concerned populations. Moreover, they have set out the role that they intend to play during the COP21 that will soon take place in Paris. However, it appears that the technology and resources they intend to use and in which they wish to invest exclusively respond to a techno-financial logic largely incompatible with a significant environmental protection policy. In effect, their offensive protectionism, which resulted in the establishment of a cartel in the energy sector, could lead to energy transition whose contents would be designed expressly for their advantage. This cartel may soon be agreed upon by states in an upcoming agreement.

References

Stopford John, Strange Susan, Henley John, Rival States, Rival Firms. Competition for World Market Shares, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Strange Susan, The Retreat of the State. The Diffusion of Power in the World Economy, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Vormedal Irja, « The Influence of Business and Industry NGOs in the Negotiation of the Kyoto Mechanisms: the Case of Carbon Capture and Storage in the CDM », Global Environmental Politics, 8 (4), 2008, pp. 36-65.

Jul 20, 2015 | Africa, Defense, English, Passage au crible (English), Security, Terrorism

By Philippe Hugon

Translation: Lawrence Myers

Passage au crible n° 129

Source: Wikimedia

Source: Wikimedia

On March 23, 2015, Al-Shabaab (“the youth” in Arabic) attacked Garissa University in Kenya, leaving more than 150 dead. These actions, targeting Christian students, were committed in an extremely violent manner in a symbolic place known for dispensing knowledge. They occurred one month after Al-Shabaab pledged its allegiance to Al-Qaida and threatened shopping centers of western origin. Let us recall that in three years, Kenya has seen three murderous attacks including the attack at the Westgate Mall in 2013. Similarly, the Ugandan capital Kampala was attacked in July 2011. As for Ethiopia, it remains under strong threat.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

With its more than 10 million inhabitants spread over 638,000 km2, Somalia has never been a state. Indeed, despite its independence in 1959, it continues to be organized into a system of clans and sub-clans. But this clan society does not appear anarchical as Somalis speak the same language – Somali – and form a homogenous ethnic group marked by its pastoral tradition. The Somali people maintain values of honor, hospitality and revenge. In this country where nearly 100% of the population remain devout followers of Islam, Islamic law coexists with tribal or clan law.

Today, however, we are seeing significant changes. Religion, which until now was a source of unity in Somalia, is bringing traditional Sufi Islam into conflict with Salafist Islam. In addition, a relative social disintegration results from the opposition between the younger and the older generations concerning code of conduct. The rise in power of the Shabaab harkens back to these determinant differences. For the past 35 years, Somalia has undergone a process of clan-based balkanization as well as socio-political chaos that has left more than 500,000 dead. Lead by a warlord, each clan is traditionally armed with a militia. The confrontations are due to disenchanted youth who have only been socialized within a context of violence.

Otherwise, several elements that have been harmful to the country are coming together and are causing further fragility. To that effect let us mention Islamic influences (Muslim Brotherhood, Salafists, the role of Eritrea), the effects of demographic pressure on rare resources or else the generalization of a parallel economy, which makes a host of illegal traffic possible. At the same time, this society finds itself drawn into globalization by dint of its diaspora. Information technology also leads to its global insertion, as does the taxation of NGOs or sea piracy with attacks on sailboats or freighters. Thus, let us recall that the tax on oil tankers (20,000 ships and 1/3 of the world’s tankers pass by the strait) made up 4,000 acts of piracy between 1900 and 2010 as reported by a census. Of course, the Atalante has successfully reduced that number since then, but it has never been able to stop them completely.

Until 1991, Somalia was led by Barré’s socialist and USSR-linked regime. Between 1992 and 1994, military interventions – whether international or American (“Restore Hope”) – all failed. A civil war raged between 1991 and 2005. In the summer of 2006, Islamic Courts, notably supported by Eritrea, then took power against faction leaders through the shura. They brought together a variety of tendencies (Hizbul Islam, “Islamic Party”), al-Islah (similar to the Muslim Brotherhood), extending to the radical Al-Shabaab Islamists, accused of being the African version of Afghanistan’s Taliban.

In place of negotiations with the moderate components of Islamic Courts, the United States and countries in the surrounding region preferred to support a government in exile that was neither representative nor legitimate. At the end of 2006, militarily supported by Ethiopia and the United States, and indirectly by Kenya, Uganda and Yemen, this transitional power regained control of Mogadishu, without controlling the warlords. An African Union Force, the AMISOM (African Union Mission in Somalia) was put in place in 2007. Al-Shabaab then began its terrorist actions, primarily in Mogadishu (end of 2009 against the African Union, suicide attack in October 20011, April 14, 2013).

Composed of an organized movement for the past ten years, Al-Shabaab may now have as many as 5,000 to 10,000 combatants. Some were trained in Afghanistan; others are from Al-Ittiyad, Somali group of Islamic movements formed in the 1980s. Others were recruited and trained by Islamic Courts in power since 2006. Then, they increased their influence when the Islamic Courts fell to the coalition of eastern African countries, supported by the United States. Their multiple demands are based on Somali nationalism and the desire to build an Islamic state founded on sharia law. They also derive their power from the control of traffic carried out by youths without prospects. Al-Shabaab then offers these youths the implementation of a global jihad by dint of their insertion into transnational networks.

Theoretical framework

1. Intergenerational violence. Within Somalia, violence results from conflict between Shabaab members, – youths socialized in violence – and the official government; the fights being essentially lead by the African force AMISOM.

2. Transnational violence. Shabaab violence also carries a regional and transnational dimension which is explained by the presence of numerous Somalis in neighboring countries (more than 600,00 refugees in Kenya), Somalis who are explicitly showing a desire to destabilize the security system of neighboring countries, beginning with Kenya. They are linked to money transfer circuits because Somalia has become a territory of proxy war between Ethiopia and Eritrea, all the while remaining a concern for countries allied with the United States that are fighting against jihadism.

Analysis

The Shabaab can be analyzed as a Somali movement. Stemming historically from Islamic Courts, they are young people whose only prospects are handling arms, violence and trafficking. They can easily be deployed within the Somali because of the government’s low level of legitimacy. Taking into account the incapacity of the State to control its territory and to ensure a minimum of state functions, they combine intimidation by violence and protection of populations. Certainly, they have set up an unpopular system based on charia law – banning the chewing of qat and listening to music -, but they also established a system to facilitate international exchanges. This is why they benefit from support allowing them a certain conventional military capacity.

Their primary resources continue to be the authority that they impose on trafficking and the local taxes that they deduct from businessmen and traders. Finally, they also draw their income from the relations that they maintain with pirates. Supported by forces from Afghanistan and Eritrea, Shabaab forces opposed the federal transitional government. At the end of 2010, they still controlled a large part of Mogadishu as well as the center and the South of the country. However, against AMISOM military action, they ultimately lost the ability to cause harm in the heart of Somalia. They then had to leave major cities, starting with Mogadishu. Following that, they disseminated into rural zones and blended into the general population. In addition to this, on September 1, 2014, they lost their leader Ahmed Abdi Godane, who was replaced by Ahmad Umar.

Their action has become particularly regional and transnational. Indeed, as in the case of Boko Haram, the regionalization of their interventions outweighs their loss of control on Somali territory. Today, it seems to have been proven that they had links with money transferring companies, certain Kenyan NGOs as well as with the diaspora. With the support of refugees or Somali emigrants, they can also progressively fit into Jihadist networks of global proportions. Via suicide attacks or terrorist actions, they are seeking to conduct asymmetric battles that seek media exposure by horror. Of course, they are not currently participating in a global jihad. However, they have created personal and organizational ties with groups affiliated with Al-Qaida or Boko Haram, which clearly indicates their long-term objectives.

Suffice it to say that neighboring countries are now threatened more and more. With over 700 kilometers of shared borders with Somalia, Kenya appears to be quite politically divided. The country is henceforth seeking to grow its military, all the while avoiding tensions between Christians – who represent three-fourths of the population – and Muslims. It is also seeking to reassure tourists and businessmen. As for Jubaland, located in southwestern Somalia on the Kenyan border, it acts as a buffer region and has a largely Somali population. The acts by Al-Shabaab committed on this territory seek to fuel religious tensions and to oppose political forces. As for Ethiopia, it has until now been spared, although it shares 1600 kilometers of its borders with Somalia. Organized into a federal state, its population is composed of a majority of Somalis primarily living in Ogaden. But this country continues to be a pivotal state allowing the United States to wage war by proxy. It is therefore unavoidable that military actions within Somalia be soon transformed into terrorist actions linked to transnational networks and Somali expatriates.

Weighing heavily on tourism and business with the West in Kenya, Ethiopia and Uganda, media coverage of horrific events seek to sow terror and to win media wars. In the case of Somalia, as in Afghanistan or with Boko Haram, it appears that military solutions lead by AMISOM can only be of limited efficiency. Indeed, sustaining solutions continue to be political. They pass by the establishment of state structures and a legitimate government.

References

Hugon Philippe, Géopolitique de l’Afrique, 3e ed., Paris, SEDES, 2013.

Mashimongo Abelard Abou-Bakr, Conflits armés africains dans le système international, Paris, L’Harmattan 2013.

Véron Jean-Bernard, « La Somalie cas d’école des Etats dits “faillis” », Politique étrangère, 76 (1), print. 2011, pp. 45-57.

Jul 7, 2015 | Communitarianism, cultural diversity, Culture en, English, Passage au crible (English), Security, Terrorism

By Alexandre Bohas

Translation: Lawrence Myers

Passage au crible n° 128

Source: Wikipedia

Source: Wikipedia

With the capture of Palmyra by Islamic State troops in Iraq and in the Levant (ISIL or Daesh in Arabic) in May, one of the most prestigious sites of antiquity is now threatened with extinction. This event testifies to ideological motives of this self-proclaimed caliphate against cultural buildings.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

In recent years, attacks against religious monuments by various groups claiming radical Islam have multiplied. These include the Buddhas of Bamiyan in 2001, which were blown up by dynamite by the Afghani Taliban regime, or the attacks on Muslim mausoleums in Timbuktu in 2012, by rebels fighting against the Malian regime during their occupation of the city. To these events, we add political instability in Egypt and Libya; a situation which favored the pillaging of numerous museums and archaeological sites, both for economic and religious reasons.

Otherwise, civil wars in Iraq and Syria have created the conditions for the long-term establishment of ISIL in certain parts of both countries. Yet, this group allegedly occupies 4,500 archaeological sites. Its supporters attacked Mesopotamian sites, but also Muslim places of worship like the tomb of Jonah in Mosul. In Syria, 90% of destruction focused on Muslim artifacts such as tombs, altars and mosques, the latter dating from the 13th and 14th centuries.

Since the end of February 2015, the sacking perpetrated in the Mosul museum as well as against the Assyrian and Parthian sites of Nimrud and Hatra have been carefully filmed and broadcast on social networks. These devastations have provoked consternation in the West as well as condemnation by UNESCO. For that matter, UNESCO is proving to be incapable of protecting these buildings classified as World Heritage Sites.

Theoretical framework

1. A reaction against the pluralization of the world. Globalization brings about a “pluralization” (Cerny) of modern societies. By promoting flows and transnational movements in cultural and socioeconomic terms, it provokes isolationism and a reaction against that which is other than oneself, emblematic of a “brutalization of the world” (Laroche). In this case, the vandalism of monuments committed by ISIL aims to do away with specificities and syncretism, both past and present, in the name of a purified, extremist and dogmatic Islam.

2. The transnationalisation of a quest for identity. These cultural destructions in Iraq, Libya and Mali are exploited in order to manipulate individuals who are both poorly integrated and disadvantaged. These individuals therefore embrace a fanatic ideology, which gives purpose to their empty existence (Hoffer). Building on a fundamentalist and antimodernist interpretation of Islam, it offers its supporters, from various backgrounds, a simplified vision of the world and also offers them a transnational identity.

Analysis

Far from being spontaneous, these sackings have been carefully calculated and organized. They are justified by the refusal to commit idolatry, forbidden by all monotheist religions. Modeled after the image of the iconoclastic controversy (8th century) and English Puritanism (17th century) in Christianity, ISIL invokes the idolatrous character of all devotion and of each place of worship, current or past, which is not directly addressed to God. In this perspective, only ISIL can be a religious practice. The sacking of Nimrod and Hatra resulted precisely from the outrageous application of this fundamental principal of Islam, which figures on ISIL’s emblem: «لا إله إلا الله » (“There is no god but God”).

ISIL films showing the devastations of Hatra or the Museum of Mosul are the result of an elaborate strategy. Along these lines, analysts have admitted their doubt regarding the authenticity of certain destroyed statues. Plaster copies were allegedly used since the original statues were supposedly sold beforehand in order to finance the war effort. Otherwise, the combatants appearing in ISIL propaganda films were identified by their accents: they allegedly come from Africa, the Indian subcontinent and the Maghreb. In other words, none of them might actually be from Mashriq, the region from Syria to Egypt. Therefore, this video is purportedly intended to recruit Muslims living far from theaters of conflict and who are often marginalized. In this regard, let us recall that Daesh forces are largely made of foreign fighters.

Besides this, it is important to consider the global attraction that ISIL exerts on certain young Muslims. This appeal can be likened to what secular religions were doing in the 1950s as described by Eric Hoffer. Today these groups of fanatic believers find a favorable echo in the extremist Islam that they advocate. All the more so since globalization reinforces their appeal by increasing their audience. The deterritorialization of relationships that characterize the strength of these communalist movements are made possible by new technologies, notably the Internet. But globalization upsets the traditional frameworks that unite cultures and societies. In so doing, it elicits isolationism that often seek to violently reaffirm undermined dogmas. Thus the cultural destructions by ISIL testify to the will to obliterate the diversity of religious, historical and cultural practices characteristic of Mesopotamia.

References

Cerny Philip G., Rethinking World Politics: A Theory of Transnational Pluralism, New York, Oxford University Press, 2010.

Evin Florence, « L’État islamique met en scène la destruction de la cité antique d’Hatra », Le Monde, 4 avril 2015.

Hoffer Eric, The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements, New York, Harber & Brothers, 1951.

Laroche Josepha, La Brutalisation du monde. Du retrait des États à la décivilisation, Montréal, Liber, 2011.

Schama Simon, « Artefacts Under Attack », Financial Times, 13 March 2015.

May 29, 2015 | Africa, China, Diplomacy, Foreign policy, Globalization, International Political Economy, Passage au crible (English)

By Moustafa Benberrah

Translation: Lawrence Myers

Passage au crible n° 127

Source:Wikimedia

Source:Wikimedia

On April 16, 2015, the city of Constantine was declared the capital of Arab culture for one calendar year. During this time, Constantine will welcome theatrical plays, festivals, symposiums, exhibitions, etc. A budget of seven billion dinars (700 million dollars) is earmarked for the organization of this event. For the occasion, the Algerian Prime Minister Abdelmalek Sellal has initiated several large projects including a cultural hub comprised of a cultural center, an urban library, a museum and galleries, alongside an art and history museum, an exhibition center and a 3,000-seat performance hall. The auditorium cost 156 million dollars and rights for its construction were given to the CSCEC (China State Construction Engineering Corp.). This cession revived the controversy over the Chinese monopoly in Algeria’s construction (building and public words) industry.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

In 2013, the PRC (People’s Republic of China) became Algeria’s largest supplier with 6.82 billion dollars of imports (+14.33%), superseding France (6.25 billion dollars), which had held the position until then. The figure reached 8.2 billion dollars in 2014. Furthermore, China is Algeria’s 10th client at 1.8 billion dollars. We note that trade, which is highly unbalanced, grew from 200 million dollars in 2000 to 10 billion dollars in 2014. This change results from the special relationship between the two countries, which began very early with the Bandung Conference held in 1955. This Asian African summit was the setting for the adoption of a resolution recognizing Algeria’s right to self-determination and independence. Moreover, China is the first non-Arab country to have recognized its provisional government (1958) and its independence in 1962. For its part, Algeria has always supported the principle of One-China, which defines Taiwan as an integral part of China. Subsequently, the non-aligned movement has substantially contributed to the political and economic rapprochement of the two nations.

Today, Sino-Algerian relations cover every strategic area including industry, agriculture, arms, infrastructures, etc. Thus, more than 790 large companies remain active in Algeria and more than twenty cooperation agreements have been signed. The latest one concerns a plan of global strategic cooperation for 2014-2018 (286 billion dollars), which boosts economic relations between the two states. This change has resulted in the influx of thousands of Chinese citizens. Today there number is estimated at 40,000 (contracted workers and CEOs accompanied by their families), including 2,000 who have obtained Algerian nationality. While the law requires focusing on local manpower, these entities are primarily hiring Chinese employees. Therefore they are significantly shaping the urban landscape by actively participating in the construction of infrastructures and by introducing an unprecedented migration in a zone that was cut off from the rest of the world during the black decade .

Theoretical framework

1. The appearance of economic diplomacy. Benefiting from the increase in oil prices on the international market, Algeria has put a recovery policy into place. The plan is based on three primary axes: 1) attracting foreign investors, 2) technology transfers and 3) the construction of necessary infrastructures for economic expansion. Consequently, legal tools have been created that would allow citizens to get more involved in projects lead by Chinese firms. However, these companies rarely respect the provisions, and this situation is leading to the development of a socio-economic debate. Ultimately, the Algerian state finds itself exceeded by and sometimes in competition with these transnational actors who are implementing their own economic logic. Oftentimes these policies even contradict the interests of the country.

2. The construction of transnational communities. Catalyst of integration, the migratory phenomenon remains one of the consequences of the globalization of economic exchanges. The work of Alain Tarrius and Michel Péraldi has explained the construction of the figure of the migrant entrepreneur in the post-Fordist context related to the industrial crisis with rising unemployment and immigration control. In Algeria, this development resulted in a redeployment of merchant channels. From that time, migrant workers were organized into transnational networks.

Analysis

Chinese companies are particularly invested in the Algerian construction sector. Since the beginning of the 2000s, the country has initiated a series of large projects funded by the rise in oil revenues. It has therefore become one of the most attractive markets of the sector for these groups, which have earned the contracts for 60 to 80% of public and private projects.

In the autumn of 2005, the head of government, Ahmed Ouyahia, said that henceforth, his country would no longer “appeal to Chinese companies in construction”. However, directing massive projects such as the East-West highway, the Great Mosque of Algiers, the Algiers opera and thousands of public housing buildings, has led to the arrival of a massive wave of Chinese labor liable to meet the requirements of cost as well as time constraints . Many worker camps have been created since the beginning of the project. Chinese boutiques have flourished in business quarters of Algiers and in other cities where Chinese companies – primarily construction – have been set up. This phenomenon is reminiscent of events in the United States in the mid-19th century following the Burlingame Treaty in 1868. Today, Chinese traders are set up in the center of Algiers, but also in other large metropolitan areas such as Constantine and Annaba. They often sell the same type of products at prices so low the reputation that Made in China connotes is forgotten. Still, this sales strategy draws as many clients as it revives the socio-economic dispute. The high unemployment rate and the competition that Algerians have undergone are at the source of numerous incidents. Last year on August 3, violent clashes between Algiers residents and Chinese immigrants erupted in the suburbs of Algiers. Actually, these endemic collisions testify to the high tensions existing between the two communities.

Several legal and cultural arrangements have been put into place to channel these troubles, to facilitate dialogue between the two societies and to help them overcome the ethnocultural divide that separates them. First and foremost, the Chinese groups are legally obliged to hire Algerians. Besides that, several programs geared towards learning Mandarin have been implemented. Consequently, Chinese is taught at the University of Algiers as well as in private schools opening their doors at increasingly fast rates. Otherwise, the Embassy of China in Algiers organizes cultural activities, like the writing contest opened to the public in 2010. Finally, an Algerian-Sino Friendship Association was created and mixed marriages are becoming more common. In other words, these sovereignty free actors compete with state authority and manage to guide Algeria’s public policies, becoming unavoidable interlocutors whose presence must be taken into account.

References

Hammou Samia, « L’immigration Chinoise en Algérie : Le cas des commerçants Chinois à Alger » consulted on 15/05/2015 and available at :

http://jcea2013.sciencesconf.org/conference/jcea2013/pages/Hammou_Samia.pdf

Rosenau James N., Turbulence in World Politics: A Theory of Change and Continuity, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1990.

Selmane Arslan, « Constantine capitale de la culture arabe 2015 : Les bobards d’une manifestation de A à Z », available at : www.elwatan.com, 26/02/15.

Strange Susan, Le Retrait de l’État. La dispersion du pouvoir dans l’économie mondiale, [1996], trad., Paris, Temps Présent, 2011.

May 19, 2015 | environment, Global Public Goods, Human safety, Passage au crible (English)

By Valérie Le Brenne

Translation: Lawrence Myers

Passage au crible n° 126

Source: Sea Shepherd

Source: Sea Shepherd

On April 6, 2015, the Thunder sank in the waters of São Tomé and Principe. Accused of illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU) and suspected of human trafficking, this vessel flying the Nigerian flag was the subject of a purple notice given by Interpol in 2003. The captain of the Bob Barker – a Sea Shepherd ship launched in pursuit of the poacher more than one hundred days ago – immediately declared that it was a matter of scuttling.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

Since 2003, Interpol member states have regularly been solicited by the organization within the framework of the notice published regarding the Thunder. More specifically, Australia, Norway and New Zealand asked authorities to communicate all information concerning its “location, its activities, people and networks and those benefitting from their illegal activities” .

Built in Norway in 1969, this ship – more than 61 meters long – was cataloged under six different names between 1986 and 2013: Arctic Ranger, Rubin, Typhoon I, Wuhan Nº4, Kuko and Thunder. Besides that, it simultaneously sailed under more than six flags: the United Kingdom, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Seychelles, Belize, Togo, Nigeria and Mongolia. For the boats implicated in illicit activities, these incessant modifications aim to escape surveillance by the Regional Fisheries Management Organization (RFMO). Accused of illegally fishing the toothfish – a fish that lives in the depths of the Southern Ocean and whose flesh, popular in Asian countries, is sold at extremely elevated prices -, the Thunder is on the list of smugglers reported by the CCAMLR (Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resource).

Anxious to preserve this species, the NGO Sea Shepherd – an organization that intervenes on behalf of the protection of fishery resources – launched Operation Icefish last September. To do this, two boats were armed to track the poachers. For more than one hundred days, the Bob Barker followed the Thunder in order to intercept it. Simultaneously, activists recovered abandoned nets that contained more than seven hundred toothfish and other dead animals.

While the Bob Barker benefitted from food provisions at the end of March, the Thunder found itself short on supplies and fuel. Unable to dock and also limited in its possibilities of transshipment, the captain allegedly decided to sink his own vessel in the hopes of destroying any incriminating evidence. According to a press release from Sea Shepherd, the organization supposedly kept its valves open to speed up the waterway and empty holds.

Theoretical framework

1. Transnational criminality. Inherited from the Roman res communis, freedom of movement and exploration constitute the fundamental rule of the high seas. Outside of territorial waters, ships are only subject to laws of the states where they are registered. However, the transformation of the registration system after World War II, carried out in order to facilitate maritime transport, fostered the emergence of flags of convenience. In so doing, poachers are able to avoid rules imposed by the RFMO. Given the high value of the most vulnerable fish species, they can therefore count of a monopoly rent that guarantees the sustainability of their criminal activities.

2. The appearance of a sovereignty-free authority. The lack of a means of coercion is prompting some sovereignty-free actors to develop their own means of control. Thus, we are witnessing a growing convergence between international organizations and private actors to fight against illegal fishing.

Analysis

In 1982, the signing of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea in Montego Bay marked a major turning point in maritime jurisdiction. By codifying customary practices, the text notably instituted the EEZ (exclusive economic zone) principle, which accords sovereignty over an area of two hundred thousand nautical miles to any state claiming it. The convention also created the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, which is responsible for judging litigation resulting from the delimitation of these areas.

However, the negotiations between maritime powers and new coastal states have not resulted in the creation of a clear status for the high seas. Contrary to the seabed, which no state is authorized to claim ownership over, the overlying waters remain free from traffic and exploitation. Only the RFMO intervenes in the management of fishery resources. But while they establish quotas and adopt technical measures, these international organizations have inadequate means for surveillance and control.

In a context marked by the intensification of global captures, this system has hardly been sufficient to curb illegal practices. Moreover, the rarefication of several species contributes to increase of their value, particularly in illegal networks. The breadth of risks reducing de facto the number of actors liable to engage in this type of poaching, the smugglers benefit from a monopoly rent, which makes this trade very lucrative.

During the 1990s, the increase in IUU captures of toothfish led the CCAMLR to adopt a series of binding measures for fleets fishing in its waters. Six times greater than the authorized volume, these catches seriously endangered stocks, all the while affecting the activity of fishermen respectful of regulations. If the establishment of TAC (Total Allowable Catches) and the obligation to take an observer on board have reduced this phenomenon, multiple pirate ships continue to withdraw from these vulnerable ecosystems. As they sail under several flags and do not respect the rules in matters of satellite signalization, the latter are completely outside the control of the concerned authorities. Moreover, they carry out their campaigns in several regions of the ocean, making operations to apprehend them particularly complex.

In these conditions, many NGOs acting in favor of the preservation of marine resources are involved in the fight against illegal fishing. Like the methods used by Greenpeace, Sea Shepherd developed a repertoire of spectacular action, which consists of tracking ships in order to prevent them from casting their nets. Although some of these actions remain questionable – the founder of Sea Shepherd, Paul Watson, remains within the scope of an international Interpol arrest warrant at the request of Costa Rica -, their impact is involved in the building of a legitimate capital. Within the framework of its program Scale, Interpol has for example partnered with the American foundation the PEW Research Center in preparation for the fight against this transnational criminality. Thus, we are currently witnessing a process of convergence of expertise between private stakeholders and international organizations.

References

OCDE, Pourquoi la pêche pirate perdure. Les ressorts économiques de la pêche illégale, non déclarée et non réglementée, Paris, OCDE, 2006.

Revue internationale et stratégique (Éd.), Mers et océans, 95 (3), 2014, 206 p.

Strange Susan, Le Retrait de l’État. La dispersion du pouvoir dans l’économie mondiale, [1996], trad., Paris, Temps Présent, 2011.

Apr 16, 2015 | Diplomacy, Foreign policy, Théorie En Marche

Author of nearly 30 books in French and English and sometimes translated into other languages (Mandarin, Spanish, etc.), Charles-Philippe David, has published noteworthy books on peace, war, strategy, security questions and American politics. In this publication dedicated to the world’s leading power, he offers the keys to understanding US foreign policy since 1945. Thus the country’s apparently contradictory, even unusual decisions – notably in regards to intervention – take on their full meaning. The book otherwise analyzes the crises that the superpower has gone through (Indochina, Cuba, etc.). It also decodes the secrets of the White House, its advisors, its experts, the United States National Security Council and its rival administrations. Besides these topics, readers will find valuable data concerning Kissinger’s supremacy and the decisional balance sheet of President Obama and his team. This stock of knowledge on the American intelligence system is therefore indispensable.

Charles Philippe David, Au sein de la Maison-Blanche, De Truman à Obama, la formulation (imprévisible) de la politique étrangère des Etats-Unis, fully revised and expanded 3rd edition, Paris, Presses de Sc. Po, 2015, 1182 pages, including 144 pages of references, an index of names and 14 tables as well as appendices.

Mar 15, 2015 | European Union, Global Public Goods, Human rights, International migrations, North-South, Passage au crible (English)

By Catherine Wihtol de Wenden

Translation: Lawrence Myers

Passage au crible n° 125

Source: Wikipedia

Source: Wikipedia

The end of 2014 and the beginning of 2015 were the setting for new migratory catastrophes in the Mediterranean. In the South of the peninsula, the Italian coast guard intercepted two cargo ships, abandoned by the smugglers who had chartered them. Yet, nearly 500 asylum seekers from Syria and Iraq were aboard each one. Their numbers are added to the 230,000 migrants who entered Europe via the Mediterranean in one year. More recently, in February 2015, the disappearance of more than 300 people and the deaths of 29 others off the coast of Libya recalled the fact that nothing had changed since 2013. Finally, at the beginning of March, Libya threatened to send cargo ships filled with immigrants to Italy if the southern European country continued with its plans of military intervention against the Islamic state. This data coincides with the end of the Mare Nostrum framework, implemented by Italy in November 2013 and November 2014. Intended to bring aid to migrants who had shipwrecked in the Mediterranean, the Frontex initiative Triton replaced this operation at the end of 2014.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

A land of confrontations and dialogues between the two shores, the Mediterranean has been at the crossroads of new migratory turbulence since the 1990s. These measures call into question the European migratory policy implemented since then. The first irregular influxes, which caught the attention of public opinion, concerned the arrival of Albanese passengers on cargo ships, attempting to reach the coast of Italy in 1991, following the fall of the Berlin Wall. Other structures loaded down with Iraqi asylum seekers followed them after the first and the second Gulf War. In this instance, it was a question mixed flows. In other words, the refugees were also seeking work. They therefore found themselves piled up on large boats, often chartered by people smugglers, since access to Europe had been restricted by the Schengen visa system since 1986.

Then, clandestine arrivals began to look more and more like small mafia businesses. They mainly involved youth moving between Morocco and Gibraltar, Senegal and the Canary Islands and especially between Libya, Tunisia and the Island of Lampedusa, located 130 km from the Tunisian coast and 200 km from Sicily. Other passageways – like Malta and Cyprus – resulted in the mixing of tourists, asylum seekers and undocumented immigrants looking for work. In addition, these movements also marked other areas. Refugees from the Middle East traveled heavily along the border of the Evros River between Turkey and Greece, and in the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla in Morocco. Bilateral agreements established between Senegal, Morocco and Spanish lessened the number of crossings by way of Gibraltar and the Canary Islands. But passage via Lampedusa was worsened by the fact that Libya, which until then had closed the borders of its territory by the agreements it had made with Italy and France, no longer controlled the flows of people on its territory. As a result, up to one million migrants could arrive from Libya on the Italian coast, declared the director of the Agency Frontex in March 2015. As for the eastern Mediterranean, it is beset by arrivals of Syrian migrants: in Turkey (1.5 million), in Jordan (800,000) and in Lebanon (1.5 million). Faced with this situation, upon each shipwreck and arrival from “harragas” (“border roasters” between the Maghreb and Europe) or families of refugees, European responses were limited to reaffirming the allowance of means to the Agency Frontex, destined to assume the “sharing of the burden”.

Theoretical framework

1. The migration gap. Phillip Martin and James Hollifield have analyzed this question related to the United States and the paradox of the liberal turned safe state. Concerning the European-Mediterranean region, on the one hand, one must consider the distance forming between the convergent analyses done by experts favorable to mobility as an essential factor of human development in the region. On the other hand, European policies driven especially under pressure from nation states plagued by the rise of the extreme right and a safe approach to immigration. But this policy carries an elevated human, financial and diplomatic cost. It especially goes against Europe’s economic and demographic needs that demand a rational choice of voluntary entry and the respect of human rights for forced immigration (refugees) and guaranteed by law (reunited families, unaccompanied minors).

2. Border control methods and their competitive bidding. The first one, the European mechanism results from a piling up of models implemented since the establishment of the Schengen system in 1985. The flows especially affect southern European countries faced with indifference and the default to solidarity of northern countries. This differential leads to separation between European countries concerning the way in which southern European countries handle those who have arrived illegally, leaving them alone in the face of skyrocketing entries, while the majority of illegal immigrants have entered legally and have prolonged their stay. The second system of control, marked by the seizure of sovereign autonomy with respect to the European rigidity, consists of signing bilateral agreements with countries on the South bank of the Mediterranean. For example, European countries have established more than 300 readmission agreements in the world in 2015 alone. For its part, France has confirmed fifteen of them, just like Italy and Spain. These texts ratify the promises made by countries on the South shore – themselves often having become countries of immigration and transit – to take back or to send back migrants who have crossed these countries en route to Sub-Saharan destinations, in exchange for residence for those who are more qualified and for development policies. Aware that they could act as gatekeepers for their European neighbors, certain countries like Libya under Gaddafi had created a migration diplomacy. However, the Libyan crisis and the Syrian drama wreaked havoc on this model, provoking 4 million refugees to flee Syria, a record in the region, only exceeded by Palestinians and Afghans.

Analysis

Among Mediterranean countries, Italy remains the country that has taken the most determined action against the tragedy, which has transformed the Mediterranean into a vast cemetery, and thus a key issue for world security. Europe’s border passing between the two shores of the Mediterranean, this sea, a “middle land”, has always been a place of passage. But due to lack of visas, today crossing it has become highly dangerous for a large number of people. It also represents an active zone where criminal networks exploit the hopelessness of the young, prey to mass joblessness and the absence of a future on the South shore. This situation is proving to be more preoccupying as the public struggles to distinguish immigration from terrorism. Without counting the fact that they hardly deviate from a national or territorialized approach of border control.

The bulk of immigration results from crises that destabilize the region; for example, Syrians and Eritreans make up half of the arrivals to Italy where the Mare Nostrum saved 170,000 people. However, with Triton, saving lives is no longer considered a priority. That is to say that Europe is unable to adopt a common policy. However, its responsibility in the deaths is clearly in contradiction with both its humanitarian approach vis-à-vis countries in the South and its declarations in matters of respect for human rights. How can it otherwise seek to meddle in international competition if it barricades itself within a fortress inhabited by an ageing population? How can it make an impact on the world stage if it refuses to consider migrations as a diplomatic priority?

References

Wihtol de Wenden Catherine, Faut-il ouvrir les frontières ? Paris, Presses de Sciences-Po, 2014.

Wihtol de Wenden Catherine, Pour accompagner les migrations en Méditerranée, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2013.

Source: Pixabay

Source: Pixabay